The Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is the protocol that networks use to exchange (announce) routing information across the Internet. Unfortunately, BGP has no mechanism to prevent the propagation of false announcements such as hijacks and misconfigurations. The Internet Route Registry (IRR) and Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI) both emerged as different solutions to improve routing security and operation in the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) by allowing networks to register information and develop route filters based on information other networks have registered.

The Internet Routing Registry (IRR) was first introduced in 1995 and remained a popular tool for BGP route filtering. However, route origin information in the IRR suffers from inaccuracies due to the lack of incentive for registrants to keep information up to date and the use of non-standardized validation procedures across different IRR database providers.

Over the past few years, the Resource Public Key Infrastructure (RPKI), a system providing cryptographically attested route origin information, has seen steady growth in its deployment and has become widely used for Route Origin Validation (ROV) among large networks.

Some networks are unable to adopt RPKI filtering due to technical or administrative reasons and continue using only existing IRR-based route filtering. Such networks may not be able to construct correct routing filters due IRR inaccuracies and thus compromise routing security.

In our paper IRR Hygiene in the RPKI Era, we at CAIDA (UC San Diego), in collaboration with MIT, study the scale of inaccurate IRR information by quantifying the inconsistency between IRR and RPKI. In this post, we will succinctly explain how we compare records and then focus on the causes of such inconsistencies and provide insights on what operators could do to keep their IRR records accurate.

IRR and RPKI trends

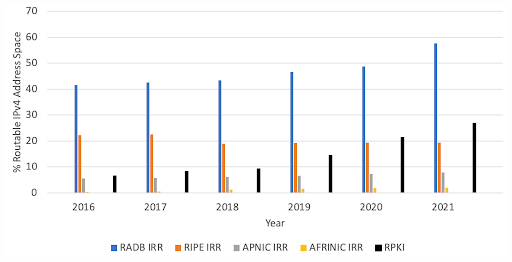

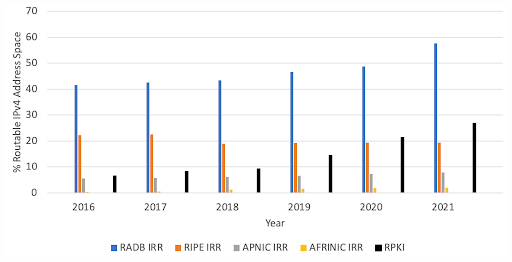

For our study we downloaded IRR data from 4 IRR database providers: RADB, RIPE, APNIC, and AFRINIC, and RPKI data from all Trust Anchors published by the RIPE NCC. Figure 1 shows IRR cover more IPv4 address space than RPKI, but RPKI grew faster than IRR, having doubled its coverage over the past 6 years.

Figure 1. IPv4 coverage of IRR and RPKI databases. RADB, the largest IRR database, has records representing almost 60% of routable IPv4 address space. In contrast, the RPKI covers almost 30% of that address space but has been steadily growing in the past few years.

Figure 1. IPv4 coverage of IRR and RPKI databases. RADB, the largest IRR database, has records representing almost 60% of routable IPv4 address space. In contrast, the RPKI covers almost 30% of that address space but has been steadily growing in the past few years.

Checking the consistency of IRR records

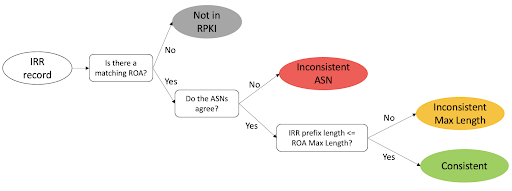

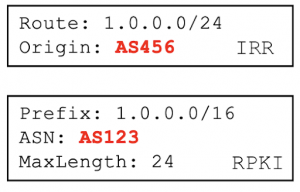

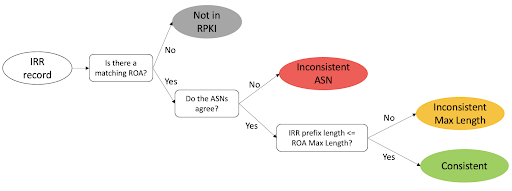

We classified IRR records following the procedure in Figure 2: first we check if there is a Route Origin Authorization (ROA) record in RPKI covering the IRR record, then in case there is one if the ASN is consistent, and finally, if the ASN is consistent, we check the prefix length compared to the maximum length attribute of RPKI records. Using this procedure we are left with 4 categories:

- Not In RPKI: If the prefix in an IRR record has no matching or covering prefix in RPKI.

- Inconsistent ASN: If the IRR record has matching RPKI records but none has the same ASN..

- Inconsistent Max Length category: If the IRR record has the same ASN as its matching RPKI records but the prefix length in the IRR record is larger than the Max Length field in the RPKI records.

- Consistent: If the IRR records have a matching RPKI record with the same ASN and according maximum length attribute.

Figure 2. Classification of IRR records

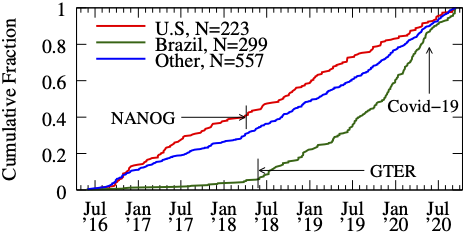

Which is more consistent? RADB vs RIPE, APNIC, AFRINIC

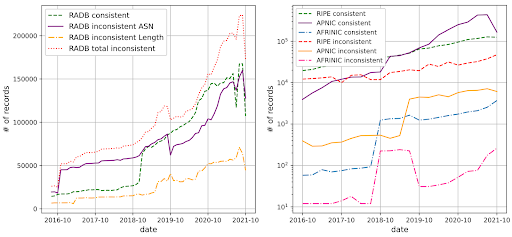

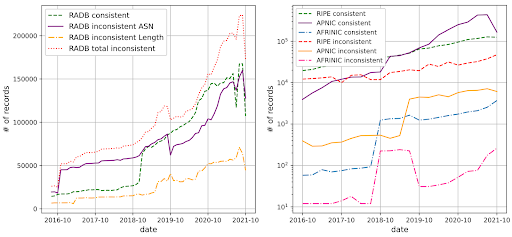

As of October 2021, we found only 38% of RADB records with matching ROAs were consistent with RPKI, meaning that there were more inconsistent records than consistent records in RADB, see Figure 3 (left) . In contrast, 73%, 98%, and 93% of RIPE, APNIC, and AFRINIC IRR records were consistent with RPKI, showing a much higher consistency than RADB, see Figure 3 (right).

We attribute the big difference in consistency to a few reasons. First, the IRR database we collected from the RIRs are their respective authoritative databases, meaning the RIRs manages all the prefixes, and verifies the registration of IRR objects with address ownership information. This verification process is stricter than that of RADB and leads to the higher quality of IRR records. Second, APNIC provides its registrants a management platform that automatically creates IRR records for a network when it registers its prefixes in RPKI. This platform contributes to a larger number of consistent records compared to other RIRs.

Figure 3. RIR-managed IRR databases have higher consistency with RPKI compared to RADB.

What caused the inconsistency?

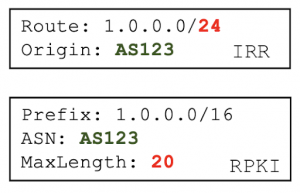

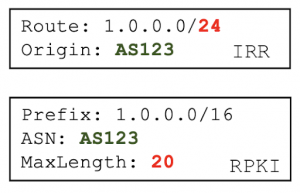

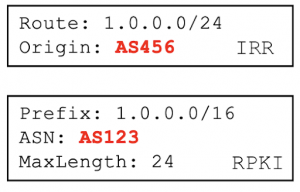

In our analysis we found that inconsistent max length was mostly caused by IRR records that are too specific, as the example shown in Figure 4, and to a lesser extent by misconfigured max length attribute in RPKI. We also found that inconsistent ASN records are largely caused by customer networks failing to remove records after returning address space to their provider network, such as the example in Figure 5.

Inconsistent Max Length (Figure 4)

- 713 caused by misconfigured RPKI Max Length.

- 39,968 caused by too-specific IRR record.

Figure 4. IRR record with inconsistent max length: the IRR prefix length exceeds the RPKI max length value.

Inconsistent ASN (Figure 5)

- 4,464 caused by customer network failing to remove RADB records after returning address space to provider network.

Figure 5. IRR record with inconsistent ASN: the IRR record ASN differs from the RPKI record ASN.

To Improve IRR accuracy

Although RPKI is becoming more widely deployed, we do not see a decrease in IRR usage, and therefore we should improve the accuracy of information in the IRR. We suggest that networks keep their IRR information up to date and IRR database providers implement policies that promote good IRR hygiene.

Networks currently using IRR for route filtering can avoid the negative impact of inaccurate IRR information by using IRRd version 4, which validates IRR information against RPKI, to ignore incorrect IRR records.