Benin: Social media blocking and Internet blackout amid 2019 elections

May 8th, 2019 by Roderick FanouIn late April 2019, social media was reportedly blocked and access to the Internet was shutdown in Benin during its 2019 parliamentary elections.

In this report, the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) and the Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) teams share OONI, IODA, and RIPE Atlas network measurement data that corroborate and provide insight into these recent censorship events in Benin.

Background

On 28th April 2019, the West African country Republic of Benin, although known as one of Africa’s most stable democracies since 1990, had parliamentary elections with no opposition candidates.

Last month, the electoral authorities, namely the Autonomous National Electoral Commission (CENA), ruled that only two parties out of seven (Le Bloc Republicain – BR – and Union Progressiste – UP) were eligible – both loyal to President Talon. Despite several attempts for dialogue, a crackdown on protests (followed by a wave of arrests) and calls to stop the electoral process, electoral authorities moved forward (with the support of the government and that of the presidents of local institutions) and Benin voters went to the polls in an election with only one choice.

In the early hours of the election day, on 28th April 2019, access to social media was reportedly blocked in the country. A few hours later, there was reportedly a complete Internet blackout. Benin thus joined the group of African countries in which the Internet was reportedly shutdown on an election day (such as Uganda and The Gambia).

In the following sections of this report, we share OONI and IODA network measurement data on the blocking of social media in Benin and the subsequent Internet outage. We augment these timely results with those of publicly available RIPE Atlas measurements launched during the first hours of the election day and continuously conducted by RIPE Atlas probes previously hosted in local networks.

Social media blocking

OONI measurements

OONI measurements, testing the accessibility of websites and apps, have been collected from multiple networks in Benin since 2017. OONI’s Web Connectivity test is designed to measure the TCP/IP, HTTP, and DNS blocking of websites, while OONI’s WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger, and Telegram tests are designed to measure the reachability of those apps from local vantage points.

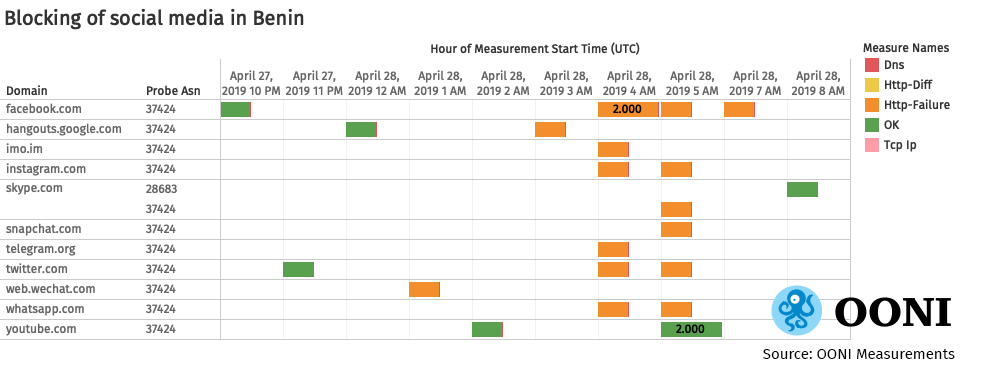

The following chart, based on OONI data collected from Benin, illustrates the blocking of social media sites on 28th April 2019, amid Benin’s 2019 parliamentary elections.

Figure 1: Blocking of social media in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Most measurements were collected from the mobile operator Spacetel (AS37424), locally known as MTN Benin, and consistently showed that the testing of the following social media sites presented HTTP failures: facebook.com, whatsapp.com, telegram.org, twitter.com, instagram.com, skype.com, snapchat.com, imo.im, hangouts.google.com, web.wechat.com. Youtube though remained accessible throughout the elections.

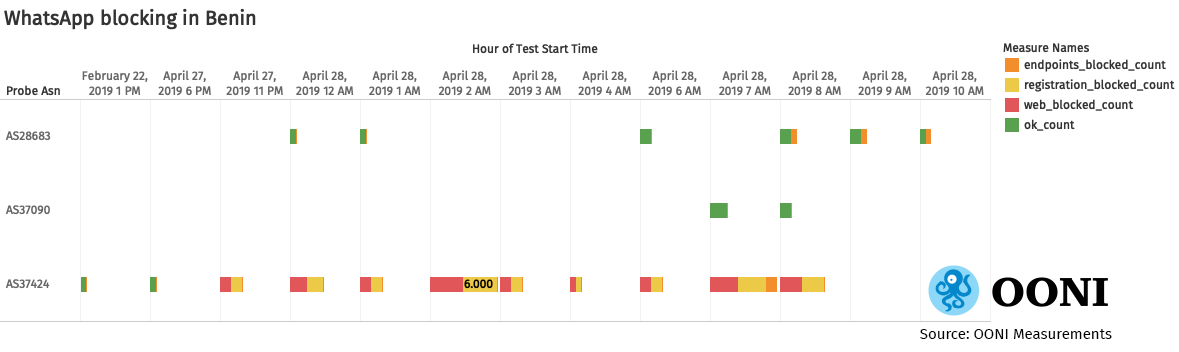

The blocking of WhatsApp was also detected through OONI’s WhatsApp test, which attempts to perform an HTTP GET request, TCP connection, and DNS lookup to WhatsApp’s endpoints, registration service, and web version over the vantage point of the user.

The following chart illustrates the blocking of WhatsApp on MTN (AS37424) in Benin.

Figure 2: WhatsApp blocking in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Figure 2: WhatsApp blocking in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Both WhatsApp’s web version (web.whatsapp.com) and the registration server used by WhatsApp’s mobile app appear to have been blocked on MTN Benin by midnight, 28th April 2019 (local time). Throughout the day, all measurements collected from this network consistently showed that attempts to establish TCP connections to WhatsApp’s registration service failed, while HTTP requests to web.whatsapp.com rendered HTTP failures, with connections being reset. MTN Benin though did not block access to the addresses used by the WhatsApp application, but limited the block to merely the registration service.

It’s worth noting though that WhatsApp was accessible on two other networks: ISOCEL (AS37090) and OPT Benin (AS28683), known as Benin Telecom. Some measurements collected from Benin Telecom (AS28683) suggest “endpoint blocking”, but those are false positives due to DNS based load balancing (for example, 169.54.55.206 belongs to WhatsApp Inc.).

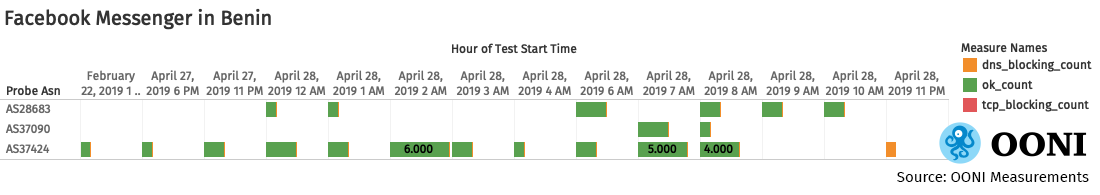

Unlike WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger appears to have been accessible on MTN Benin (AS37424) on 28th April 2019, even though access to facebook.com was blocked.

The following chart shows that Facebook Messenger was accessible in Benin on three different networks during the elections.

Figure 3: Facebook Messenger testing in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Figure 3: Facebook Messenger testing in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

All measurements show that TCP connections to Facebook’s endpoints succeeded (the few DNS anomalies were false positives), suggesting that Facebook Messenger worked while facebook.com was blocked.

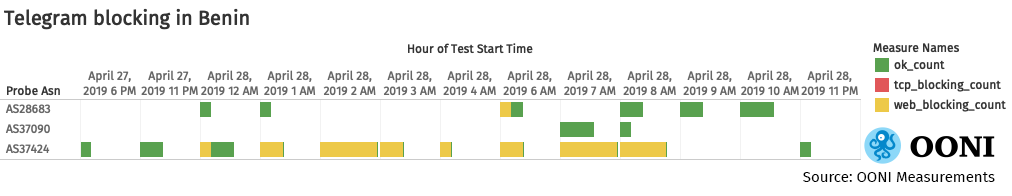

Quite similarly, measurements collected through OONI’s Telegram test show that MTN Benin blocked telegram.org, but they did not block access to the Telegram mobile app. This is illustrated through the following chart, which also shows that Telegram’s web version seemed mostly accessible on other networks.

Figure 4: Telegram blocking in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Figure 4: Telegram blocking in Benin, Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI) measurements, Benin: https://explorer.ooni.io/country/BJ

Several circumvention tool sites, such as purevpn.fr, betternet.co, and tigervpn.com, presented HTTP failures. However, these failures are likely false positives, particularly given the fact that more popular circumvention tool sites, such as psiphon.ca, were accessible. The testing of openvpn.com presented an anomaly, but this was triggered by a cloudflare captcha page (i.e., the site was accessible in Benin during the elections).

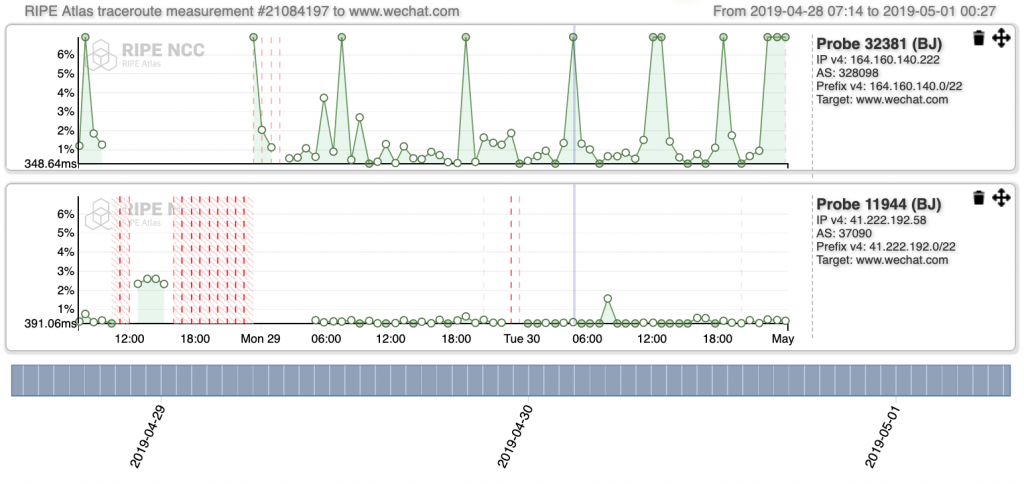

RIPE Atlas measurements

As of 29th April 2019, the RIPE Atlas measurements platform contains 10,458 probes deployed worldwide for the purpose of measuring the Internet. The RIPE Atlas probes can run pings, traceroutes, DNS, HTTP, SSL measurements, etc. Five of them were previously deployed within local networks in Benin. Among them, two were online on 28th April 2019, hosted in JENY-SAS-AS (AS328098)(whose provider is Spacetel, AS37424) and ISOCEL Telecom (AS37090).

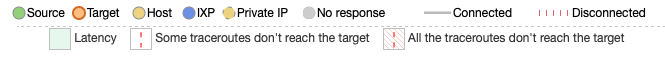

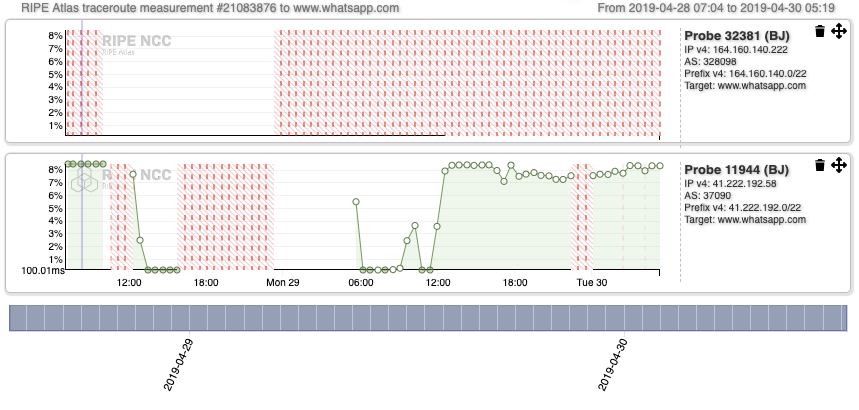

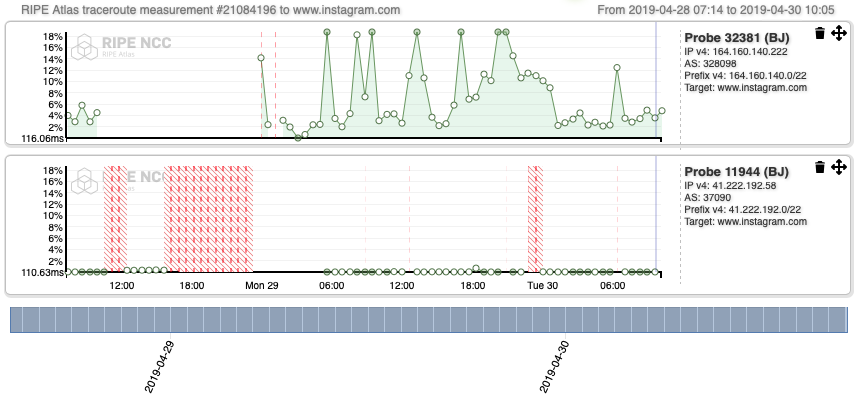

Since HTTP queries are only enabled on RIPE Atlas anchors (none of which are hosted in Benin), we launched traceroutes from all online RIPE Atlas probes in the country towards the landing webpages of social media, such as whatsapp.com, instagram.com, wechat.com, messenger.com, facebook.com. The measurements cover the period April 28, 2019 at 07:04 UTC to April 30, 2019 at 05:19 UTC. The results of these measurements reflect the connectivity on the IP/network layer (and not on the application layer) from the host Autonomous System (AS).

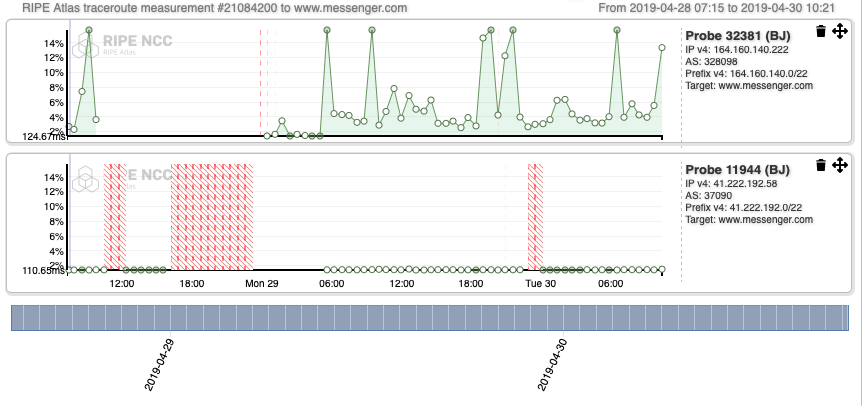

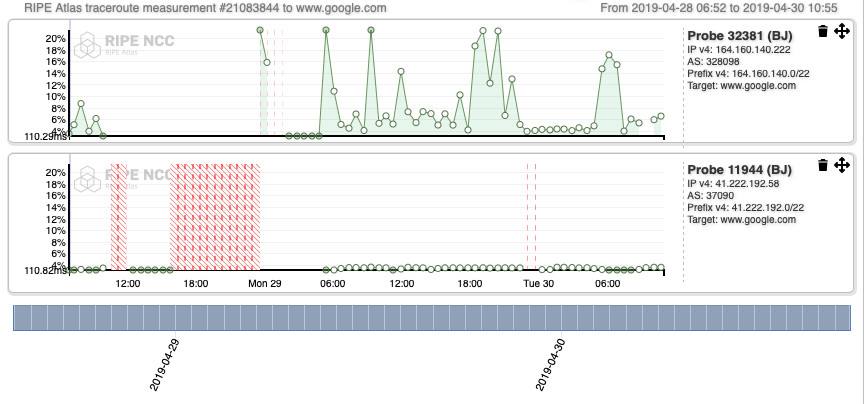

Figures 5, 6, 7, 8, and 9 display for each probe the evolution of the RTT from the source IP to their different destination IPs (y-axis) over the period of the measurements campaign (x-axis). Figure 10, 11, and 12 present not only the RTTs to the destination IPs, but also the inferred AS paths at key moments of the said campaign. We analyze and compare those figures in the next paragraphs, highlighting the insights they provide.

For whatsapp.com, we could not collect any successful measurement outputs from Probe 32381 (top graph in Figure 5) until the end of that period (name resolution failed on the node). By contrast, the results from Probe 11944, hosted in AS37090, were successful (with a median of 113.45 ms) from April 28, 2019 at 7:12 to 10:11 UTC but stopped reaching the target from 10:11 UTC to 12:04 UTC, suggesting that the blocking affected the network layer.

Then followed a period (12:04 UTC to 15:13 UTC) during which RTTs to the same destination gradually decreased from 107.72 ms to 0 ms, indicating that during a short period packets could be transmitted. From April 28, 2019 at 15:13 UTC to April 29, 2019 at 05: 04 UTC, the probe could not reach the destination IP or was fully disconnected again on the IP layer. This corresponds to the biggest period of the blackout (presented in the following Internet blackout section). Traceroutes were only successful again starting from April 29, 2019 at 05:04 UTC.

Interestingly, the patterns registered for Probe 11944 when it comes to traceroutes towards the landing webpages of instagram.com (Figure 6), wechat.com (Figure 7), www.messenger.com (Figure 8), www.google.com (Figure 9), Google DNS (Figure 10 and 11), show that the Internet outage is experienced by the source AS (ISOCEL).

Figure 5: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.whatsapp.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083876/, April 28, 2019. The red pattern is registered for Probe 32381 because the probe could not resolve the URL www.whatsapp.com.

Figure 5: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.whatsapp.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083876/, April 28, 2019. The red pattern is registered for Probe 32381 because the probe could not resolve the URL www.whatsapp.com.

Figure 6: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.instagram.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084196/, April 28, 2019

Figure 6: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.instagram.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084196/, April 28, 2019

Figure 7: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.wechat.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084197/, April 28, 2019

Figure 7: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.wechat.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084197/, April 28, 2019

Figure 8: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.messenger.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084200/, April 28, 2019

Figure 8: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.messenger.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084200/, April 28, 2019

Figure 9: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.google.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/, April 28, 2019

Figure 9: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to www.google.com, https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/, April 28, 2019

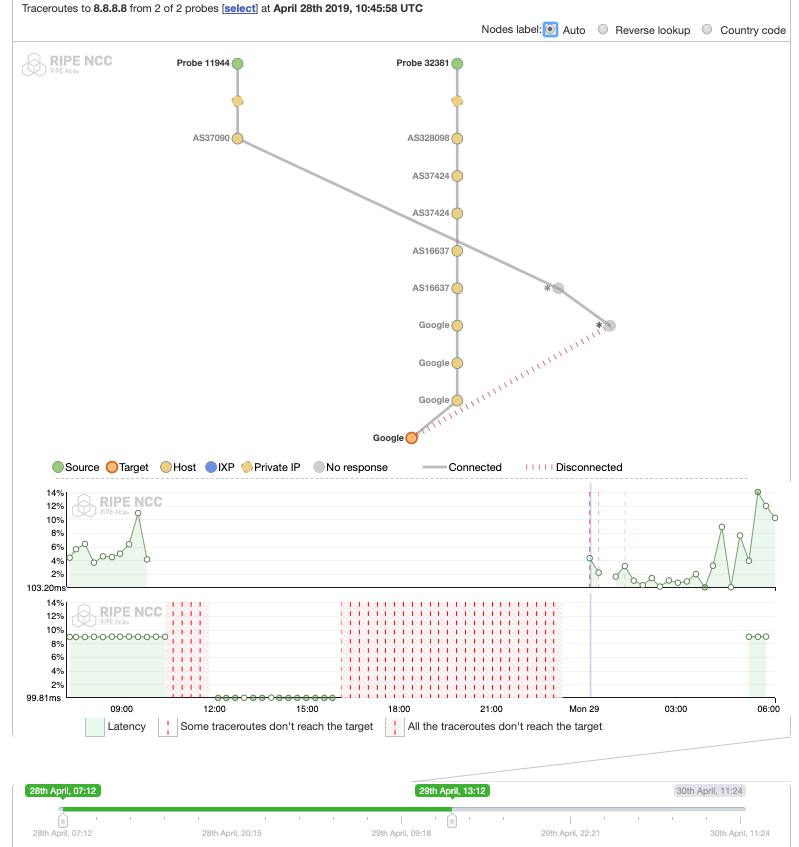

Compared to those of Probe 32381, they are mostly consistent, except for the interval of time between ~12:00 UTC – 00:00 UTC, which is the time during which there was an Internet outage. These results are confirmed by in-depth inspection carried out on AS paths inferred from the traceroute outputs. They suggest that ASes ISOCEL on one side, JENY-AS and Spacetel experience the shutdown differently.

Measurements from Probe 11944, which are gathered from AS37090, are consistent with OONI Probe measurements in the previous section, confirming the accessibility of these services on ISOCEL Telecom.

Figure 10: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to Google DNS (8.8.8.8), https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/ (AS paths inferences before the shutdown), April 28, 2019

Figure 10: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to Google DNS (8.8.8.8), https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/ (AS paths inferences before the shutdown), April 28, 2019

Figure 11: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to Google DNS (8.8.8.8), https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/ (AS paths inferences during the shutdown), April 28, 2019

Figure 11: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to Google DNS (8.8.8.8), https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21083844/ (AS paths inferences during the shutdown), April 28, 2019

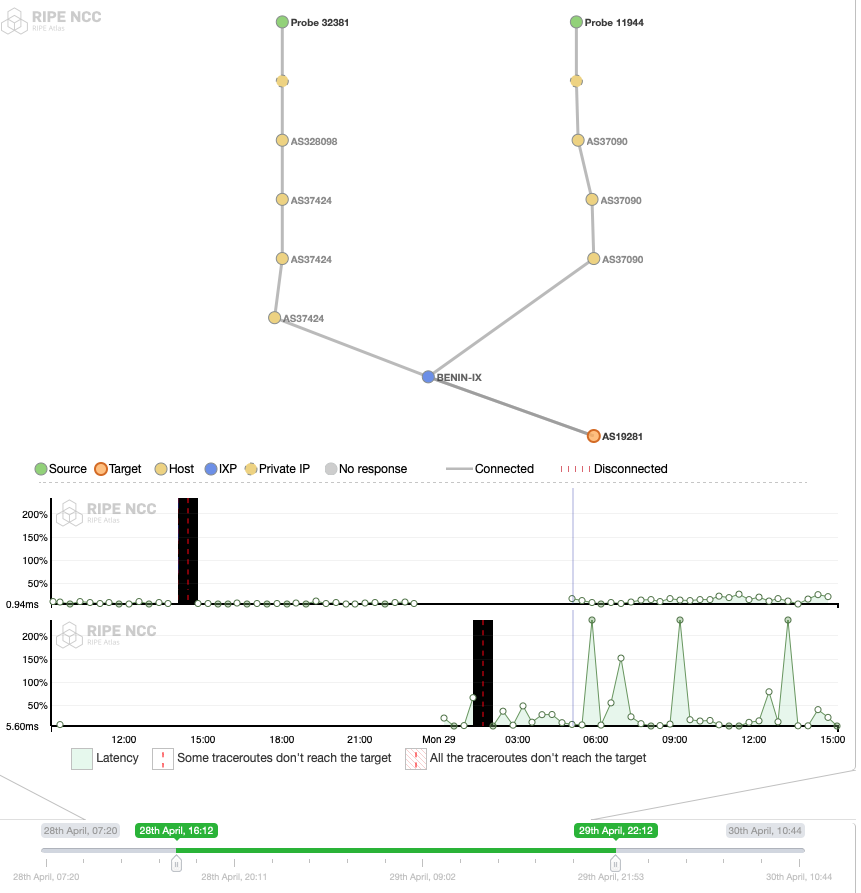

Figure 12: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to 9.9.9.9 (Quad9) depicting that BENIN-IX was mostly UP on election day and that the shutdown did not occur there and proving that each network implemented/suffered from the blackout differently. https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084227/, April 28, 2019

Figure 12: RIPE Atlas measurement, Recurring IPv4 traceroute measurement from all probes online in Benin to 9.9.9.9 (Quad9) depicting that BENIN-IX was mostly UP on election day and that the shutdown did not occur there and proving that each network implemented/suffered from the blackout differently. https://atlas.ripe.net/measurements/21084227/, April 28, 2019

We can deduce the following from comparing these figures:

- ISOCEL end-users clearly suffered a shutdown on election day, because its network did.

- Meanwhile, the destinations of our measurements were all reachable from JENY-AS and Spacetel Benin: MTNNS-AS (AS16637), the sibling of Spacetel was reachable from both ASes on the IP layer, while landing webpages from social media were not.

- There was a period (00:00 UTC to 06:00 UTC) during which ISOCEL was experiencing a blackout on the IP layer, while Spacetel was not.

- Both networks have been reconnected to the Internet since early April 29, 2019 roughly at 06:00 UTC.

- The Internet Exchange point switch was UP during the whole period of the blocking campaign (Figure 12).

Internet blackout

IODA detected significant Internet blackouts affecting Benin on 28th and 29th April 2019. IODA’s data sources further show that these blackouts were not limited to a single AS; instead, many large ASes in Benin experienced blackouts.

About IODA

The Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) runs a project called IODA (short for Internet Outage Detection and Analysis), which monitors the Internet, in near-realtime, to identify macroscopic Internet outages, affecting the edge of the network (i.e. significantly impacting an AS or a large fraction of a country). IODA does so using three complementary data sources:

- Global Internet routing (BGP): Using data from ~500 monitors participating in the RouteViews and RIPE RIS projects to establish which network blocks are reachable based on the Internet control plane.

- Active probing: Continuously probing a large fraction of the (routable) IPv4 address space using a methodology developed by the University of Southern California to infer when a /24 block is affected by a network outage.

- Internet Background Radiation: Processing unsolicited traffic reaching the UCSD Network Telescope monitoring an unutilized /8 address block.

Data from IODA provides insight into Internet disruptions affecting entire countries, as well as the granularity required for identifying disruptions only affecting certain networks or regions within countries.

Internet blackout in Benin

IODA data shows that an Internet blackout occurred in Benin during the elections, on 28th April 2019.

The following figures show the time series for the three data sources that IODA monitors for IP addresses belonging to different aggregates of addresses in Benin.

Figure 13: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), Benin: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 13: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), Benin: https://ioda.caida.org

In Figure 13, all three time series indicate the occurrence of a significant Internet blackout. The figure shows that the outage began at around 10 AM UTC on 28th April 2019 (the day of the election). By around 6 AM UTC on the next day, 29th April 2019, the time series for all data sources suggest that the Internet blackout in Benin ended.

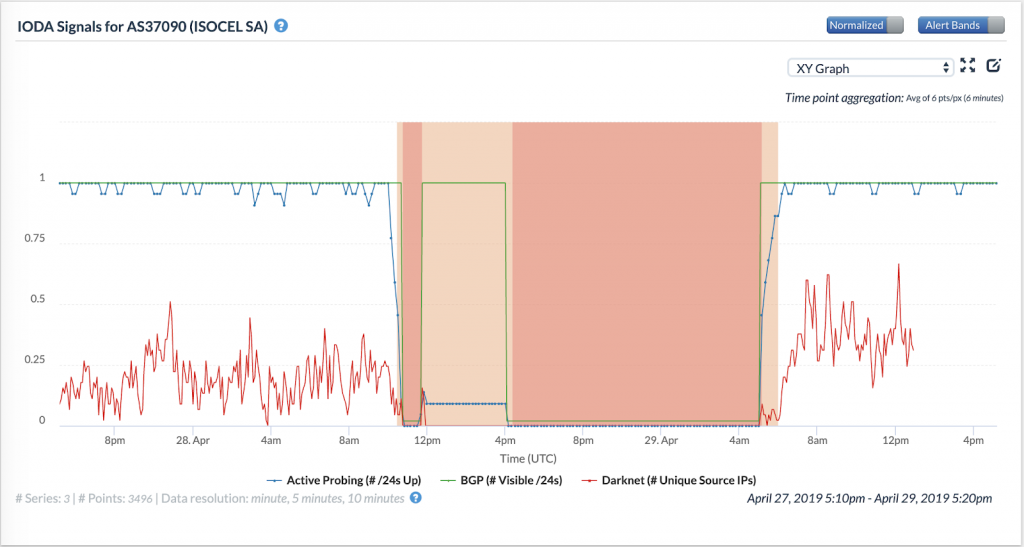

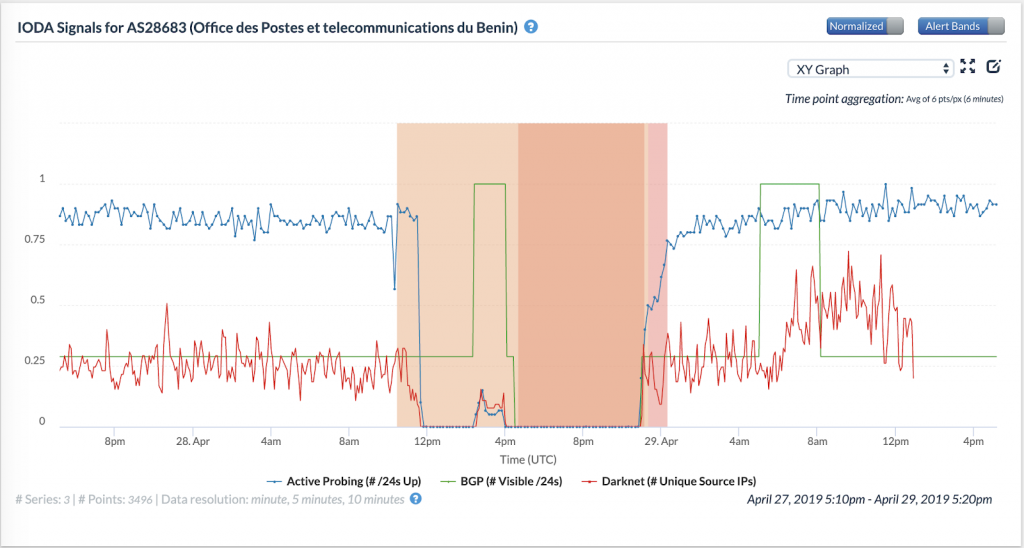

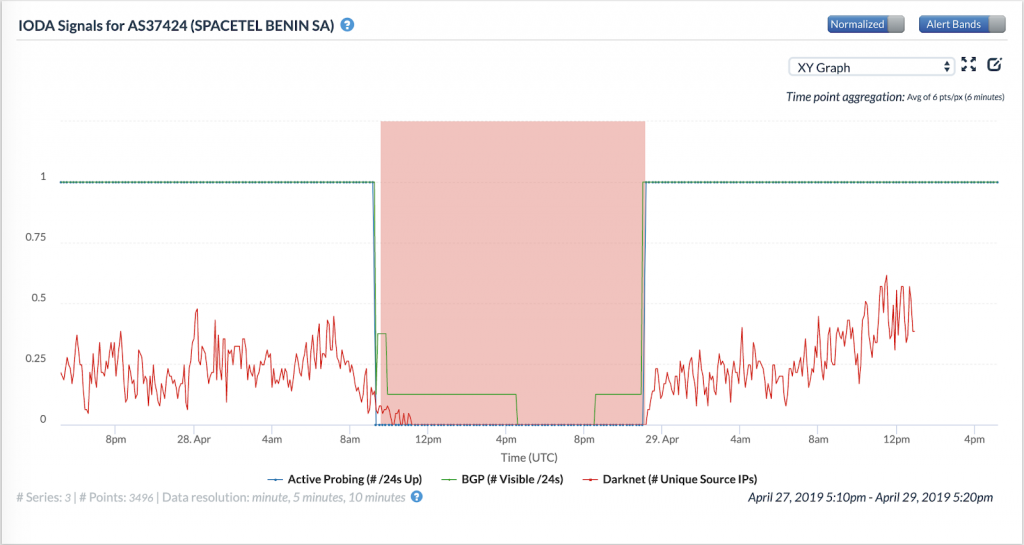

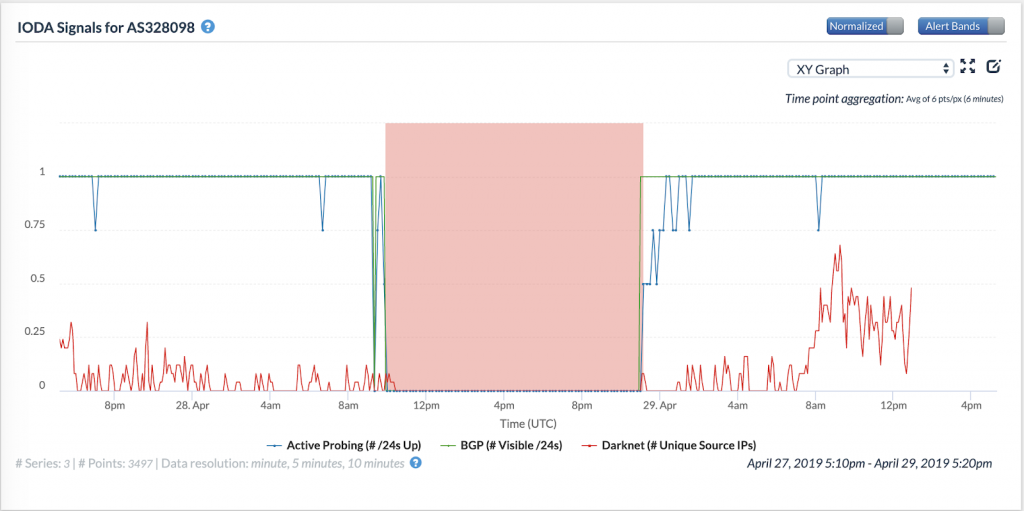

Figures 14, 15, 16 and 17 below show the occurrences of Internet blackout events in four large ASes in Benin.

Figure 14: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS37090: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 14: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS37090: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 15: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS28683: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 15: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS28683: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 16: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS37424: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 16: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS37424: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 17: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS328098: https://ioda.caida.org

Figure 17: Internet Outage Detection and Analysis (IODA), AS328098: https://ioda.caida.org

The figures show that the blackout events began at roughly the same time (around 10 AM UTC) in all the four ASes. However, one of them seems to have recovered connectivity few hours later than the others, suggesting that individual ASes might have implemented shutdowns in their networks independently of each other.

Figures 11 and 12 show that the blackout ended in AS28683 and AS37424 before midnight UTC on 29th April 2019, whereas the blackout ended in AS37090 at around 6 AM UTC. We also observe differences in how the blackout events manifest in IODA’s data sources. AS37090 and AS37424 see a significant drop in BGP-visible /24 blocks at the beginning of the outage. However, AS37090’s visible /24 blocks curve briefly reattains prior values before dropping again. AS28683, on the other hand, experiences only a drop in its active-probing curve initially.

In summary:

- Four different large ASes in Benin had blackouts. These blackouts were not limited to a single AS; instead, many large ASes in Benin experienced blackouts.

- The blackouts begin at roughly the same time, but end at different times; it is, therefore, possible that ASes implemented them independently.

- Each AS’s blackout has a different signature in IODA’s data sources; for some, the blackout is visible in the BGP data source first whereas for others, the blackout is visible in the active probing data source first.

MTN Benin (AS37424) acknowledged the Internet disruptions on 28th April 2019, but declined all responsibility, promising to reimburse its clients.

This post is reposted from the April 30th, 2019 OONI blog at https://ooni.io/post/2019-benin-social-media-blocking/ by Roderick Fanou (CAIDA, UC San Diego), Ramakrishna Padmanabhan (CAIDA, UC San Diego), Arturo Filastò (OONI), and Maria Xynou (OONI).