the inevitable conflict between data privacy and science

January 4th, 2009 by kcBalancing individual privacy against other needs, such as national security, critical infrastructure protection, or even science, has long been a challenge for law enforcement, policymakers and scientists. It’s good news when regulations prevent unauthorized people from examining the contents of your communications, but current privacy laws often make it hard — sometimes impossible — to provide academic researchers with data needed to scientifically study the Internet. Our critical dependence on the Internet has rapidly grown much stronger than our comprehension of its underlying structure, performance limits, dynamics, and evolution, and unfortunately current privacy law is part of the problem — legal constraints intended to protect individual communications privacy also leave researchers and policymakers trying to analyze the global Internet ecosystem essentially in the dark. To make matters worse, the few data points suggest a dire picture, shedding doubt on the Internet’s ability to sustain its role as the world’s preferred communications substrate. In the meantime, Internet science struggles to make progress given much less available empirical data than most fields of scientific inquiry.

Supported by DHS’s S&T Directorate, We investigated the state of the field of network traffic data anonymization in 2008, including: (1) augmenting our networking bibliography with a few dozen papers on various aspects of anonymization; (2) creating a taxonomy of tools for anonymizing Internet data and log files; (3) creating a summary of best practices for PREDICT researchers; and (4) working with Internet2 on establishing its own IRB for network research using Internet2 data.

I also moderated a panel in October 2008 on “Network Data Sharing Issues” at ACM’s workshop on Network Data Anonymization. Immediately following another panel where lawyers from Europe, Japan, and the United States presented the data privacy laws of their respective jurisdictions, I coordinated a panel discussion of how researchers are navigating such legal issues (or not) in their scientific networking research. (I owe thanks to Christos Papadapolous who made my job much easier by arranging for a recording of a related panel (3 hour mp3 file) two weeks earlier at CCW, which we cited widely. Their extensive discussion made our panel significantly more productive than it would have been otherwise.)

The workshop group (about 30 people, lots of international representation) found rough consensus that two documents are needed, and several attendees from the workshop are already contributing to a draft of the first one.

- A proposed code of conduct for the network measurement community, per Mark and Vern’s suggestion last year. A useful model is the 1979 Belmont report which propounded ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research.

Applied to the Internet, such a report would ideally include a list of the most important questions for empirical Internet researchers to be studying this decade, and what specific data is needed to study them, but creating a list is a topic for another workshop we’ll try in 2009. In the meantime, if you have a minute, CAIDA put up a Google moderator page soliciting the most important empirical questions to be asking about the Internet. (The obvious cybersecurity need for data is to test out intrusion/anomaly detection tools, which require some understanding of what “normal” traffic looks like. DHS’s PREDICT project is trying to enable data sharing for such security research, but its main obstacles are legal issues too murky even for DHS to navigate.) - Building a case for legislative change. All three attorneys in the earlier panel echoed Paul Ohm’s comments at CCW (see 3 hour mp3 file above) that by the time Internet measurement-related legislation does land on Congressional radar (don’t hold our breath, they warned) the network research community had better have a compelling story for what we want changed and why. Orin Kerr reminded us that the best cases for legislative change included numbers in units of dead bodies (hence

FISA being rewritten at the blinding legislative speed of 16 months!), or billions of dollars (hard to measure when organizations are disincented to acknowledge their systems are vulnerable enough to cost them significantly).

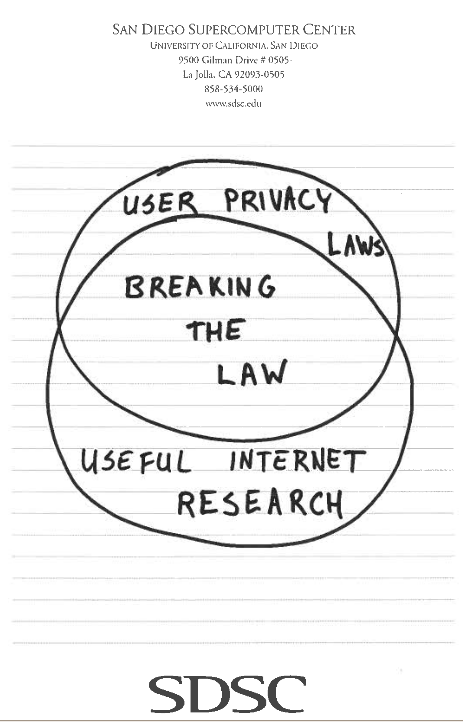

Inspired by the workshop and the Indexed blog, CAIDA data administrator and researcher Emile Aben scribbled the below view of current network research, suggesting how much more useful Internet research could be done than we’re capable of doing at the moment.

I admit this issue gives me mixed feelings while watching EFF sue everyone they can find related to wiretapping undertaken as part of post-9/11 surveillance activities. As a scientist and idealist, I’m generally in favor of greater transparency when given a choice, so publication of what actually transpired is appealing. But, I have spent a decade of that scientific career gaining an appreciation for just how little situational awareness those agencies charged with infrastructure protection can possibly have regarding global Internet dynamics and operational threats. Like scientists, they are especially constrained if they follow the most conservative interpretations of laws written before the Internet was created, and certainly before it was a viable vector for economic, social, and even physical damage to humans. I find myself wishing EFF would worry less about how little time it takes for NSA to know what’s happening on the Internet and more about how much time it takes for everyone else to know. Maybe now that FISA has congealed they can throw some effort into the policy work required to make the Internet a safe place to do science.

We first have to figure out what the word privacy means now, what we care about and why. We have to figure out what it is that this conception privacy is supposed to mean when we’re all through. And then we have to figure out what we, collectively, mean to do about it. About my idea of privacy, there are services provided by Google which don’t meet my idea of privacy. And I can’t imagine receiving my mail there. But nobody has ever told me I had to receive my mail at Google. It’s an opt-in interface. You bring them data, of yours, voluntarily, and you get pretty amazing new services connected with your data, in return for allowing them to keep any inference they can make by mining your data. If you think that’s a fair bargain, you’re free to accept. If you think it’s not a fair bargain, you’re free to decline. I have no problem with the bargain, most of the time I decline it, some of the time I accept it. Often I accept it with a vanilla wafer instead of a cookie, right? We have to manage our own idea about what constitutes privacy and autonomy in the 21st century. In order to do that we have to have accurate information. We have to know what people do, we have to have enough transparency to understand what they do, and we have to teach children about how to think about these issues as fundamental issues of ethics and morality in a technological society. I personally spend a lot of time on this, I teach privacy, I think about it, I write about it, I talk about it, I try to lawyer for it. But it is growing very difficult, because the net is pulling us together in ways that human beings have never been together before. And what we have thought of as “privacy”, meaning exclusive control over our identity, is being shattered into a million pieces. And those pieces are flying in different directions, and even studying how it works is difficult, and most people don’t do it. So the consequence is that what we have called privacy is dying before our eyes, and being replaced by something which is a mere facsimile. It’s not Google’s fault that this is true, it’s not Microsoft’s fault that this is true, it’s not the Free Software Foundation’s fault that this is true, and you can’t blame it on the Internet, because the Internet is just all of us. But we have built a society which is transforming who we are, and like most other forms of ecological disaster, that happens to us mostly while we refuse to open our eyes to the evidence that it is going on. We’re going to have to get very serious about this, very soon. I keep waiting, it keeps not happening.

Eben Moglen, http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Freeing_the_Mind:_Free_Software_and_the_end_of_proprietary_culture

September 24th, 2009 at 8:26 am

With all thats going on in the world in these days, internet privacy is really what the world needs. We don’t need spies, spooks, or governments looking over our shoulders. We can handle our own individualism and can maintain our daily lives without government oversight.